How is wind formed?

Changes in air pressure and temperature usually start and maintain wind. Generated by differential heating of the Earth’s surface, pressure differences may develop on all scales, from local to global. Warm air is less dense than cold air and tends to rise, reducing the number of air molecules at ground level. This leaves behind a mass deficit, or an area of low pressure. As air cools, it sinks and the number of air molecules at the Earth’s surface increases, forming a region of high pressure. To balance the difference, air flows from high to low pressure, creating wind.

What is atmospheric pressure?

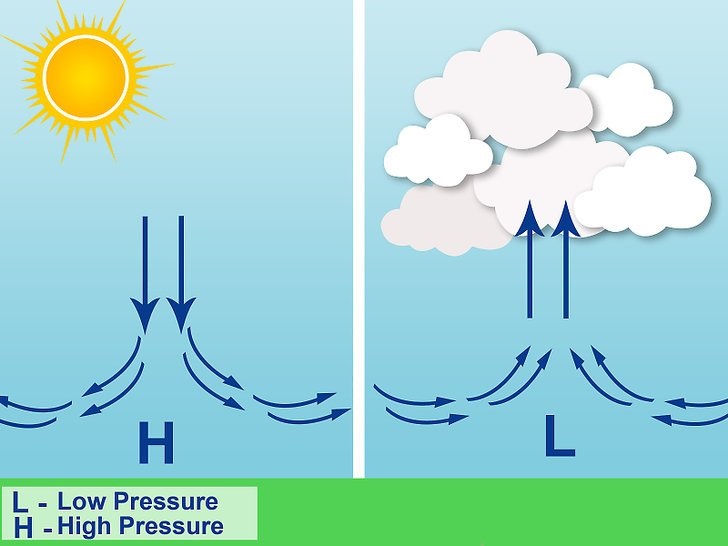

Atmospheric pressure at any particular point is caused by the weight of air molecules above it. As discussed earlier, differences in pressure create wind as the air moves from areas of high to low pressure. Weather experienced on the ground is greatly influenced by atmospheric pressure: high pressure usually produces fine weather, and low pressure creates unsettled, often stormy conditions. Rising air in a low-pressure system, warm air converges at the surface and spirals upward. Rising water vapour cools and condense, forming clouds, and often precipitation. As air molecules are transported downward, high pressure forms at the surface. Descending air warms, causing water droplets to evaporate and clouds to dissipate. Since winds always blow from areas of high pressure to low pressure, a closed circulation system develops.

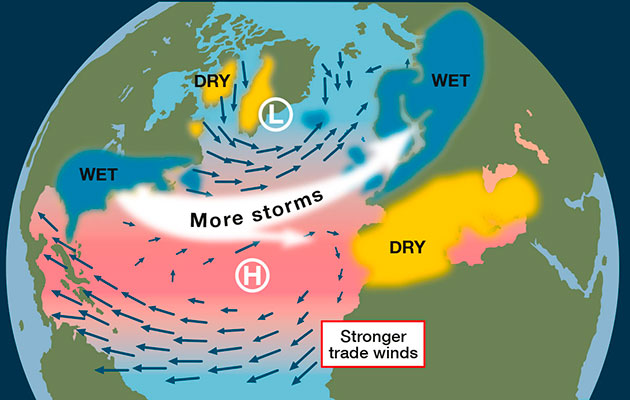

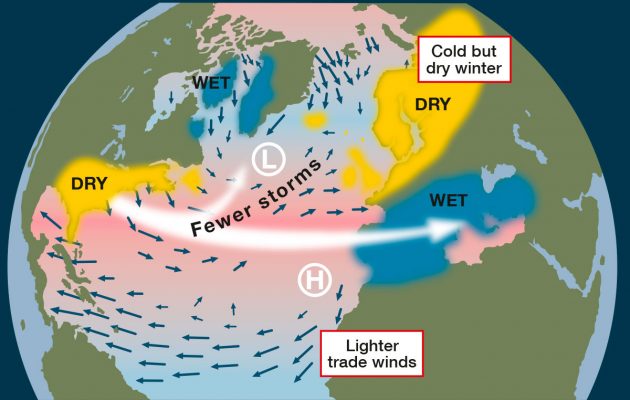

Areas of high and low pressure encircle Earth in defined bands. In equatorial regions, low pressure dominates, but in midlatitudes, large areas of high pressure in both hemispheres. Belts of low pressure systems are found toward the polar regions. Two pressure systems largely influence the climate of the Maltese Islands. These are the Icelandic Low and the Azores High. The Azores high is a semi-permanent subtropical high is named after the archipelago of the Azores. This region of high pressure gains strength and shifts farther north in summer, occasionally expanding to the northeast, preventing Atlantic storms from reaching Europe. The Icelandic Low is a semi-permanent area of low pressure between Iceland and Greenland. This centre of atmospheric circulation is associated with frequent storm activity and is stronger in winter. The behaviour of the Azores High and Icelandic Low anchor the NAO. If we measure the pressure differences between the Icelandic Low and the Azores High, we see fluctuations in their strengths. We say that there is a positive NAO index when there is a stronger than normal Azores High and a deeper Icelandic low. As storm systems track further north it gives warmer and wetter weather in Europe keeping the most of Europe on the south side of lows in the warmer and wetter south-westerly tropical maritime air. A negative index, on the other hand, is indicated by a less well developed high to the south or low pressure to the north. This weaker pressure gradient and more southerly position of the Azores High means that the winter storms will tend to track further south. This tends to bring unsettled weather into the Mediterranean and southern Europe while the colder, drier air will affect the UK giving us less stormy but drier and colder weather.

In the upcoming note we will be discussing global winds and the general circulation of the atmosphere.

0 comments

Write a comment